In an action-packed day and a half, NASA's Cassini spacecraft will be making its closest swoop over the surface of Saturn's moon Dione and scrutinizing the atmosphere of Titan, Saturn's largest moon.

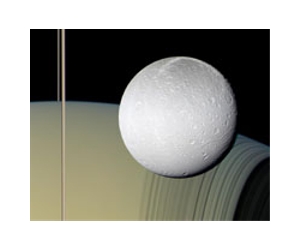

The closest approach to Dione, about 61 miles (99 kilometers) above the surface, will take place at about 1:39 a.m. PST (4:39 a.m. EST) on Dec. 12. One of the questions Cassini scientists will be asking during this flyby is whether Dione's surface shows any signs of activity.

The closest approach to Dione, about 61 miles (99 kilometers) above the surface, will take place at about 1:39 a.m. PST (4:39 a.m. EST) on Dec. 12. One of the questions Cassini scientists will be asking during this flyby is whether Dione's surface shows any signs of activity.

Understanding Dione's internal structure will help address that question, so Cassini's radio science instrument will learn how highly structured the moon's interior is by measuring variations in the moon's gravitational tug on the spacecraft.

The Astronomical Research Center (A.R.C) mentioned that the composite infrared spectrometer instrument will also look for heat emissions along fractures on the moon's surface.

Cassini will also be probing whether Dione, like another Saturnian moon, Rhea, has a tenuous atmosphere. Scientists expect a Dionean atmosphere - if there is one - to be much more ethereal than even Rhea's.

Research published in journal Geophysical Research Letters and led by Sven Simon, a Cassini magnetometer team member at the University of Cologne, Germany, found magnetic field disturbances around Dione, hinting at a tenuous atmosphere.

But scientists hope to get stronger confirmation by "tasting" the space around the moon with Cassini's ion and neutral mass spectrometer.

On Cassini's journey out from Dione toward Titan, the imaging science subsystem will turn back to look at Dione's distinctive, wispy fractures and a ridge called Janiculum Dorsa.

Cassini will approach within about 2,200 milles (3,600 kilometers) of the Titan surface, at about 12:11 p.m. PST (3:11 PM EST) on Dec. 13.

At Titan, the composite infrared spectrometer will be making measurements to understand how the seasonal transition from spring to summer affects wind patterns in the atmosphere near Titan's north pole. It will also search for mist.

The visual and infrared mapping spectrometer and imaging science subsystem will be observing the same equatorial deserts where the imaging science subsystem saw sudden and dramatic surface changes last year, when Titan was experiencing early northern spring. One possibly theory is that rainstorms caused these changes.

As Cassini recedes from Titan, the imaging cameras will also continue to observe the moon for another day to monitor any new weather systems. The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency.