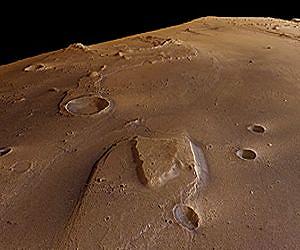

Newly released images taken by ESA's Mars Express show an unusual accumulation of young craters in the large outflow channel called Ares Vallis. Older craters have been reduced to ghostly outlines by the scouring effects of ancient water.

In the distant past, probably over 3.8 billion years ago, large volumes of water must have rushed through the Ares Vallis with considerable force. Mars Express imaged the preserved aftermath of this scene on 11 May 2011.

In the distant past, probably over 3.8 billion years ago, large volumes of water must have rushed through the Ares Vallis with considerable force. Mars Express imaged the preserved aftermath of this scene on 11 May 2011.

The prominent Oraibi crater lies in the channel and is about 32 km across. It is filled with sediments and its southern rim has been eroded by water. NASA's Pathfinder mission landed in this region in 1997, 100 km to the north of the crater and off the right-hand side of this image.

The Astronomical Research Center (A.R.C) mentioned that The great outflow that partially eroded Oraibi also cut stepped riverbanks and excavated parallel channels in the riverbed that indicate the flow path. Streamlined islands have been left standing above the valley floor, again indicating the direction taken by the flow.

On the floor and on the plateau to the left of the image there are a number of 'ghost craters'. These were once fully formed craters, but water or wind eroded their rims and filled them by depositing sediments.

Their presence on the plateau suggests that even that higher ground may have been at least partially overrun by flooding. The solitary mounds that can be seen likely represent the remaining sections of the plateau's original surface.

In addition to these heavily eroded, ancient features, however, there is evidence in the image for an impact on the martian surface in the much more recent past.

On the far left side of the image, parts of an ejecta blanket can be seen, made of material excavated from the ground during the formation of an impact crater. In the upper left corner of the image, there is a landslide roughly 4 km wide, probably caused by the same impact, and surrounding the landslide, single streaks of ejecta can be traced out.

Furthermore, there are numerous small craters in the image, appearing both in clusters and in aligned groups. An abundance of such craters can result when an asteroid or other projectile breaks up into many pieces in the atmosphere before crashing to the ground.

Clusters of craters may also be created when a large impact ejects rock fragments with such force that they travel from a few kilometres to hundreds of kilometres before returning to the surface, creating new impacts called secondary craters.

The clusters of craters in this image are relatively young and likely formed within the past 20 million years: erosion would have erased them if they had occurred a long time ago.