Scientists at the SETI Institute, Mountain View, Calif., and NASA's Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif. believe that traces of Mars' wet past are hidden from the scrutiny of space-borne instruments under a thin varnish of iron oxide, or rust.

The Astronomical Research Center (A.R.C) mentioned that new research suggests that Mars could be spotted with many more patches of carbonates - minerals that form readily in large bodies of water and can point to a planet's wet history - than originally suspected.

The Astronomical Research Center (A.R.C) mentioned that new research suggests that Mars could be spotted with many more patches of carbonates - minerals that form readily in large bodies of water and can point to a planet's wet history - than originally suspected.

Although only a few small outcrops of carbonates have been detected on Mars (Related articles: Ehlmann et al. (2008) Science and Brown et al. (2010) EPSL ), scientists believe many more examples are blocked from view by a screen of iron-rich varnish. The findings appear online on July 1st at the International Journal of Astrobiology.

"The plausibility of life on Mars depends on whether liquid water dotted its landscape for thousands or millions of years," said Janice Bishop, a planetary scientist at Ames and the SETI Institute as well as the paper's lead author.

"It's possible that an important clue - the presence of carbonates - has largely escaped the notice of investigators trying to learn if liquid water once pooled on the Red Planet."

The varnish is so widespread that each of the Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, have a motorized grinding tool to remove the rust-like overcoat on rocks before the rovers' other instruments can inspect them. In fact, the varnish resembles the thin, dark coating commonly found on desert rocks on Earth.

Researchers realized the importance of the varnish after Chris McKay, a planetary scientist at Ames, investigated carbonate rocks coated with iron oxides that had been collected at Little Red Hill in California's Mojave Desert. Scientists use this region for field experiments because its extremely dry conditions are similar to Mars.

"When we examined the carbonate rocks in the lab, it became evident that an iron oxide skin may be hindering the search for clues to the Red Planet's hydrological history," said McKay. Bishop found "that the varnish both altered and partially masked the spectral signature of the carbonates."

Every mineral is made up of atoms that vibrate at specific frequencies to produce a unique fingerprint that allows scientists to accurately identify its composition.

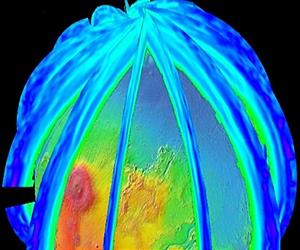

Indeed, the rock coating spectra measured in Bishop's lab were similar to those observed by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft as it orbited above Nili Fossae, an ancient region of Mars, where the strongest carbonate signature have been found.

Although MRO recently detected small patches of carbonates - approximately 200-500 feet wide - on the Martian surface, the Mojave study suggests that more patches may have been overlooked because their spectral signature could have been changed by the pervasive varnish.

"To better determine the extent of carbonate deposits on Mars - and by inference, the ancient abundance of liquid water - we need to investigate the spectral properties of carbonates mixed with other minerals," said Bishop.

Her team is now studying this in the lab. Their results could help instruments such as the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, or CRISM, which is aboard MRO, in its search for traces of a wet Martian past.

McKay also found dehydration-resistant blue-green algae under the rock varnish at Little Red Hill. Scientists believe the varnish may have temporarily extended the time that Mars was habitable, as the planet's surface slowly dried up.

"These organisms are protected from deadly ultraviolet light by the iron oxide coating," said McKay. "This survival mechanism might have played a role if Mars once had life on the surface."

Consequently, in addition to being used to help characterize Mars' water history, carbonate rocks also could be a good place to look for the signatures of early life on the Red Planet.